-

[AdapterFusion] Non-Destructive Task Composition for Transfer Learning*NLP/NLP_Paper 2024. 7. 26. 17:40

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.00247

Abstract

Sequential fine-tuning and multi-task learning are methods aiming to incorporate knowledge from multiple tasks; however, they suffer from catastrophic forgetting and difficulties in dataset balancing. To address these shortcomings, we propose AdapterFusion, a new two stage learning algorithm that leverages knowledge from multiple tasks. First, in the knowledge extraction stage we learn task specific parameters called adapters, that encapsulate the task-specific information. We then combine the adapters in a separate knowledge composition step. We show that by separating the two stages, i.e., knowledge extraction and knowledge composition, the classifier can effectively exploit the representations learned from multiple tasks in a non-destructive manner. We empirically evaluate AdapterFusion on 16 diverse NLU tasks, and find that it effectively combines various types of knowledge at different layers of the model. We show that our approach outperforms traditional strategies such as full fine-tuning as well as multi-task learning. Our code and adapters are available at AdapterHub.ml.

1. Introduction

The most commonly used method for solving NLU tasks is to leverage pretrained models, with the dominant architecture being a transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017), typically trained with a language modelling objective (Devlin et al., 2019; Radford et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019b). Transfer to a task of interest is achieved by fine-tuning all the weights of the pretrained model on that single task, often yielding state-of-the-art results (Zhang and Yang, 2017; Ruder, 2017; Howard and Ruder, 2018; Peters et al., 2019). However, each task of interest requires all the parameters of the network to be fine-tuned, which results in a specialized model for each task.

There are two approaches for sharing information across multiple tasks. The first consists of starting from the pretrained language model and sequentially fine-tuning on each of the tasks one by one (Phang et al., 2018). However, as we subsequently fine-tune the model weights on new tasks, the problem of catastrophic forgetting (McCloskey and Cohen, 1989; French, 1999) can arise, which results in loss of knowledge already learned from all previous tasks. This, together with the nontrivial decision of the order of tasks in which to fine-tune the model, hinders the effective transfer of knowledge. Multi-task learning (Caruana, 1997; Zhang and Yang, 2017; Liu et al., 2019a) is another approach for sharing information across multiple tasks. This involves fine-tuning the weights of a pretrained language model using a weighted sum of the objective function of each target task simultaneously. Using this approach, the network captures the common structure underlying all the target tasks. However, multi-task learning requires simultaneous access to all tasks during training. Adding new tasks thus requires complete joint retraining. Further, it is difficult to balance multiple tasks and train a model that solves each task equally well. As has been shown in Lee et al. (2017), these models often overfit on low resource tasks and underfit on high resource tasks. This makes it difficult to effectively transfer knowledge across tasks with all the tasks being solved equally well (Pfeiffer et al., 2020b), thus considerably limiting the applicability of multi-task learning in many scenarios.

Recently, adapters (Rebuffi et al., 2017; Houlsby et al., 2019) have emerged as an alternative training strategy. Adapters do not require fine-tuning of all parameters of the pretrained model, and instead introduce a small number of task specific parameters — while keeping the underlying pretrained language model fixed. Thus, we can separately and simultaneously train adapters for multiple tasks, which all share the same underlying pretrained parameters. However, to date, there exists no method for using multiple adapters to maximize the transfer of knowledge across tasks without suffering from the same problems as sequential fine-tuning and multi-task learning. For instance, Stickland and Murray (2019) propose a multi-task approach for training adapters, which still suffers from the difficulty of balancing the various target tasks and requiring simultaneous access to all target tasks.

In this paper we address these limitations and propose a new variant of adapters called AdapterFusion. We further propose a novel two stage learning algorithm that allows us to effectively share knowledge across multiple tasks while avoiding the issues of catastrophic forgetting and balancing of different tasks. Our AdapterFusion architecture, illustrated in Figure 1, has two components. The first component is an adapter trained on a task without changing the weights of the underlying language model. The second component — our novel Fusion layer — combines the representations from several such task adapters in order to improve the performance on the target task.

Contributions Our main contributions are: (1) We introduce a novel two-stage transfer learning strategy, termed AdapterFusion, which combines the knowledge from multiple source tasks to perform better on a target task. (2) We empirically evaluate our proposed approach on a set of 16 diverse NLU tasks such as sentiment analysis, commonsense reasoning, paraphrase detection, and recognizing textual entailment. (3) We compare our approach with Stickland and Murray (2019) where adapters are trained for all tasks in a multi-task manner, finding that AdapterFusion is able to improve this method, even though the model has simultaneous access to all tasks during pretraining. (4) We show that our proposed approach outperforms fully fine-tuning the transformer model on a single target task. Our approach additionally outperforms adapter based models trained both in a Single-Task, as well as Multi-Task setup.

The code of this work is integrated into the AdapterHub.ml (Pfeiffer et al., 2020a).

2. Background

In this section, we formalize our goal of transfer learning (Pan and Yang, 2010; Torrey and Shavlik, 2010; Ruder, 2019), highlight its key challenges, and provide a brief overview of common methods that can be used to address them. This is followed by an introduction to adapters (Rebuffi et al., 2017) and a brief formalism of the two approaches to training adapters.

Task Definition.

We are given a model that is pretrained on a task with training data D0 and a loss function L0. The weights Θ0 of this model are learned as follows:

In the remainder of this paper, we refer to this pretrained model by the tuple (D0, L0).

We define C as the set of N classification tasks having labelled data of varying sizes and different loss functions:

C = {(D1, L1), . . . ,(DN , LN )}

The aim is to be able to leverage a set of N tasks to improve on a target task m with Cm = (Dm, Lm). In this work we focus on the setting where m ∈ {1, . . . , N}.

Desiderata.

We wish to learn a parameterization Θm that is defined as follows:

where Θ' is expected to have encapsulated relevant information from all the N tasks. The target model for task m is initialized with Θ' for which we learn the optimal parameters Θm through minimizing the task’s loss on its training data.

2.1. Current Approaches to Transfer Learning

There are two predominant approaches to achieve sharing of information from one task to another.

2.1.1. Sequential Fine-Tuning

This involves sequentially updating all the weights of the model on each task. For a set of N tasks, the order of fine-tuning is defined and at each step the model is initialized with the parameters learned through the previous step. However, this approach does not perform well beyond two sequential tasks (Phang et al., 2018; Pruksachatkun et al., 2020) due to catastrophic forgetting.

2.1.2. Multi-Task Learning (MTL)

All tasks are trained simultaneously with the aim of learning a shared representation that will enable the model to generalize better on each task (Caruana, 1997; Collobert and Weston, 2008; Nam et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016, 2017; Zhang and Yang, 2017; Ruder, 2017; Ruder et al., 2019; Sanh et al., 2019; Pfeiffer et al., 2020b, inter alia).

However, MTL requires simultaneous access to all tasks, making it difficult to add more tasks on the fly. As the different tasks have varying sizes as well as loss functions, effectively combining them during training is very challenging and requires heuristic approaches as proposed in Stickland and Murray (2019).

2.2. Adapters

While the predominant methodology for transfer learning is to fine-tune all weights of the pretrained model, adapters (Houlsby et al., 2019) have recently been introduced as an alternative approach with applications in domain transfer (Ruckle et al., 2020b), machine translation (Bapna and Firat, 2019; Philip et al., 2020) transfer learning (Stickland and Murray, 2019; Wang et al., 2020; Lauscher et al., 2020), and cross-lingual transfer (Pfeiffer et al., 2020c,d; Ust ¨ un et al. ¨ , 2020; Vidoni et al., 2020). Adapters share a large set of parameters Θ across all tasks and introduce a small number of task-specific parameters Φn. While Θ represents the weights of a pretrained model (e.g., a transformer), the parameters Φn, where n ∈ {1, . . . , N}, are used to encode task-specific representations in intermediate layers of the shared model. Current work on adapters focuses either on training adapters for each task separately (Houlsby et al., 2019; Bapna and Firat, 2019; Pfeiffer et al., 2020a) or training them in a multi-task setting to leverage shared representations (Stickland and Murray, 2019). We discuss both variants below.

2.2.1. Single-Task Adapters (ST-A)

For each of the N tasks, the model is initialized with parameters Θ0. In addition, a set of new and randomly initialized adapter parameters Φn are introduced.

The parameters Θ0 are fixed and only the parameters Φn are trained. This makes it possible to efficiently parallelize the training of adapters for all N tasks, and store the corresponding knowledge in designated parts of the model. The objective for each task n ∈ {1, . . . , N} is of the form:

For common adapter architectures, Φ contains considerably fewer parameters than Θ, e.g., only 3.6% of the parameters of the pretrained model in Houlsby et al. (2019).

2.2.2. Multi-Task Adapters (MT-A)

Stickland and Murray (2019) propose to train adapters for N tasks in parallel with a multi-task objective. The underlying parameters Θ0 are finetuned along with the task-specific parameters in Φn. The training objective can be defined as:

2.2.3. Adapters in Practice

Introducing new adapter parameters in different layers of an otherwise fixed pretrained model has been shown to perform on-par with, or only slightly below, full model fine-tuning (Houlsby et al., 2019; Stickland and Murray, 2019; Pfeiffer et al., 2020a). For NLP tasks, adapters have been introduced for the transformer architecture (Vaswani et al., 2017). At each transformer layer l, a set of adapter parameters Φl is introduced. The placement and architecture of adapter parameters Φ within a pretrained model is non-trivial. Houlsby et al. (2019) experiment with different architectures, finding that a two-layer feed-foward neural network with a bottleneck works well. They place two of these components within one layer, one after the multi-head attention (further referred to as bottom) and one after the feed-forward layers of the transformer (further referred to as top).1 Bapna and Firat (2019) and Stickland and Murray (2019) only introduce one of these components at the top position, however, Bapna and Firat (2019) include an additional layer norm (Ba et al., 2016).

Adapters trained in both single-task (ST-A) or multi-task (MT-A) setups have learned the idiosyncratic knowledge of the respective tasks’ training data, encapsulated in their designated parameters. This results in a compression of information, which requires less space to store task-specific knowledge. However, the distinct weights of adapters prevent a downstream task from being able to use multiple sources of extracted information. In the next section we describe our two stage algorithm which tackles the sharing of information stored in adapters trained on different tasks.

3. AdapterFusion

Adapters avoid catastrophic forgetting by introducing task-specific parameters; however, current adapter approaches do not allow sharing of information between tasks. To mitigate this we propose AdapterFusion.

3.1. Learning algorithm

In the first stage of our learning algorithm, we train either ST-A or MT-A for each of the N tasks.

In the second stage, we then combine the set of N adapters by using AdapterFusion. While fixing both the parameters Θ as well as all adapters Φ, we introduce parameters Ψ that learn to combine the N task adapters to solve the target task.

Ψm are the newly learned AdapterFusion parameters for task m. Θ refers to Θ0 in the ST-A setting or Θ0→{1,...,N,m} in the MT-A setup. In our experiments we focus on the setting where m ∈ {1, ..., N}, which means that the training dataset of m is used twice: once for training the adapters Φm and again for training Fusion parameters Ψm, which learn to compose the information stored in the N task adapters.

By separating the two stages — knowledge extraction in the adapters, and knowledge composition with AdapterFusion — we address the issues of catastrophic forgetting, interference between tasks and training instabilities.

3.2. Components

AdapterFusion learns to compose the N task adapters Φn and the shared pretrained model Θ, by introducing a new set of weights Ψ. These parameters learn to combine the adapters as a dynamic function of the target task data.

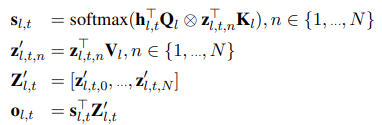

As illustrated in Figure 2, we define the AdapterFusion parameters Ψ to consist of Key, Value and Query matrices at each layer l, denoted by K_l , V_l and Q_l respectively. At each layer l of the transformer and each time-step t, the output of the feedforward sub-layer of layer l is taken as the query vector. The output of each adapter z_l,t is used as input to both the value and key transformations. Similar to attention (Bahdanau et al., 2015; Vaswani et al., 2017), we learn a contextual activation of each adapter n using

Where ⊗ represents the dot product and [·, ·] indicates the concatenation of vectors.

Given the context, AdapterFusion learns a parameterized mixer of the available trained adapters. It learns to identify and activate the most useful adapter for a given input.

Adapter에 Attention하는 거네..!??!

4. Experiments

In this section we evaluate how effective AdapterFusion is in overcoming the issues faced by other transfer learning methods. We provide a brief description of the 16 diverse datasets that we use for our study, each of which uses accuracy as the scoring metric.

4.1. Experimental Setup

In order to investigate our model’s ability to overcome catastrophic forgetting, we compare Fusion using ST-A to only the ST-A for the task. We also compare Fusion using ST-A to MT-A for the task to test whether our two-stage procedure alleviates the problems of interference between tasks. Finally, our experiments to compare MT-A with and without Fusion let us investigate the versatility of our approach. Gains in this setting would show that AdapterFusion is useful even when the base adapters have already been trained jointly.

In all experiments, we use BERT-base-uncased (Devlin et al., 2019) as the pretrained language model. We train ST-A, described in Appendix A.2 and illustrated in Figure 5, for all datasets described in §4.2. We train them with reduction factors2 {2, 16, 64} and learning rate 0.0001 with AdamW and a linear learning rate decay. We train for a maximum of 30 epochs with early stopping. We follow the setup used in Stickland and Murray (2019) for training the MT-A. We use the default hyperparameters3 , and train a MT-A model on all datasets simultaneously.

For AdapterFusion, we empirically find that a learning rate of 5e − 5 works well, and use this in all experiments.4 We train for a maximum of 10 epochs with early stopping. While we initialize Q and K randomly, we initialize V with a diagonal of ones and the rest of the matrix with random weights having a small norm (1e − 6). Multiplying the adapter output with this value matrix V initially adds small amounts of noise, but retains the overall representation. We continue to regularize the Value matrix using l2-norm to avoid introducing additional capacity.

4.2. Tasks and Datasets

We briefly summarize the different types of tasks that we include in our experiments, and reference the related datasets accordingly. A detailed descriptions can be found in Appendix A.1.

Commonsense reasoning is used to gauge whether the model can perform basic reasoning skills: Hellaswag (Zellers et al., 2018, 2019), Winogrande (Sakaguchi et al., 2020), CosmosQA (Huang et al., 2019), CSQA (Talmor et al., 2019), SocialIQA (Sap et al., 2019). Sentiment analysis predicts whether a given text has a positive or negative sentiment: IMDb (Maas et al., 2011), SST (Socher et al., 2013). Natural language inference predicts whether one sentence entails, contradicts, or is neutral to another: MNLI (Williams et al., 2018), SciTail (Khot et al., 2018), SICK (Marelli et al., 2014), RTE (as combined by Wang et al. (2018)), CB (De Marneffe et al., 2019). Sentence relatedness captures whether two sentences include similar content: MRPC (Dolan and Brockett, 2005), QQP5 . We also use an argument mining Argument (Stab et al., 2018) and reading comprehension BoolQ (Clark et al., 2019) dataset.

5. Results

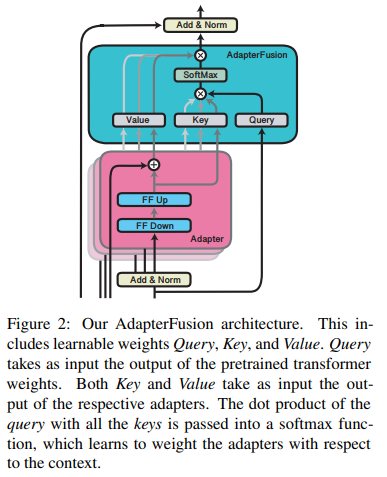

We present results for all 16 datasets in Table 1. For reference, we also include the adapter architecture of Houlsby et al. (2019), ST-AHoulsby, which has twice as many parameters compared to ST-A. To provide a fair comparison to Stickland and Murray (2019) we primarily experiment with BERT-base-uncased. We additionally validate our best model configurations — ST-A and Fusion with ST-A — with RoBERTa-base, for which we present our results in Appendix Table 4.

5.1. Adapters

Training only a prediction-head on the output of a pretrained model can also be considered an adapter. This procedure, commonly referred to as training only the Head, performs considerably worse than fine-tuning all weights (Howard and Ruder, 2018; Peters et al., 2019). We show that the performance of only fine-tuning the Head compared to Full finetuning causes on average a drop of 10 points in accuracy. This demonstrates the need for more complex adaptation approaches.

In Table 1 we show the results for MT-A and ST-A with a reduction factor 16 (see the appendix Table 3 for more results) which we find has a good trade-off between the number of newly introduced parameters and the task performance. Interestingly, the ST-A have a regularization effect on some datasets, resulting in better performance on average for certain tasks, even though a much small proportion of weights is trained. On average, we improve 0.66% by training ST-A instead of the Full model.

For MT-A we find that there are considerable performance drops of more than 2% for CSQA and MRPC, despite the heuristic strategies for sampling from the different datasets (Stickland and Murray, 2019). This indicates that these heuristics only partially address common problems of multitask learning such as catastrophic interference. It also shows that learning a shared representation jointly does not guarantee the best results for all tasks. On average, however, we do see a performance increase of 0.4% using MT-A over Full finetuning on each task separately, which demonstrates that there are advantages in leveraging information from other tasks with multi-task learning.

5.2. AdapterFusion

AdapterFusion aims to improve performance on a given target task m by transferring task specific knowledge from the set of all N task adapters, where m ∈ {1, . . . , N}. We hypothesize that if there exists at least one task that supports the target task, AdapterFusion should lead to performance gains. If no such task exists, then the performance should remain the same.

Dependence on the size of training data.

In Table 1 we notice that having access to relevant tasks considerably improves the performance for the target task when using AdapterFusion. While datasets with more than 40k training instances perform well without Fusion, smaller datasets with fewer training instances benefit more from our approach. We observe particularly large performance gains for datasets with less than 5k training instances. For example, Fusion with ST-A achieves substantial improvements of 6.5 % for RTE and 5.64 % for MRPC. In addition, we also see performance gains for moderately sized datasets such as the commonsense tasks CosmosQA and CSQA. Fusion with MT-A achieves smaller improvements, as the model already includes a shared set of parameters. However, we do see performance gains for SICK, SocialIQA, Winogrande and MRPC. On average, we observe improvements of 1.27% and 1.25% when using Fusion with ST-A and MT-A, respectively.

Mitigating catastrophic interference. In order to identify whether our approach is able to mitigate problems faced by multi-task learning, we present the performance differences of adapters and AdapterFusion compared to the fully fine-tuned model in Figure 3. In Table 2, we compare Adapter Fusion to ST-A and MT-A. The arrows indicate whether there is an improvement ↗, decrease ↘, or if the the results remain the same →. We compare the performance of both, Fusion with ST-A and Fusion with MT-A, to ST-A and MT-A. We summarize our four most important findings below.

(1) In the case of Fusion with ST-A, for 15/16 tasks, the performance remains the same or improves as compared to the task’s pretrained adapter. For 10/16 tasks we see performance gains. This shows that having access to adapters from other tasks is beneficial and in the majority of cases leads to better results on the target task. (2) We find that for 11/16 tasks, Fusion with ST-A improves the performance compared to MT-A. This demonstrates the ability of Fusion with ST-A to share information between tasks while avoiding the interference that multi-task training suffers from. (3) For only 7/16 tasks, we see an improvement of Fusion with MT-A over the ST-A. Training of MT-A in the first stage of our algorithm suffers from all the problems of multi-task learning and results in less effective adapters than our ST-A on average. Fusion helps bridge some of this gap but is not able to mitigate the entire performance drop. (4) In the case of AdapterFusion with MT-A, we see that the performances on all 16 tasks improves or stays the same. This demonstrates that AdapterFusion can successfully combine the specific adapter weights, even if the adapters were trained in a multi-task setting, confirming that our method is versatile.

Summary. Our findings demonstrate that Fusion with ST-A is the most promising approach to sharing information across tasks. Our approach allows us to train adapters in parallel and it requires no heuristic sampling strategies to deal with imbalanced datasets. It also allows researchers to easily add more tasks as they become available, without requiring complete model retraining.

While Fusion with MT-A does provide gains over simply using MT-A, the effort required to train these in a multi-task setting followed by the Fusion step are not warranted by the limited gains in performance. On the other hand, we find that Fusion with ST-A is an efficient and versatile approach to transfer learning.

6. Analysis of Fusion Activation

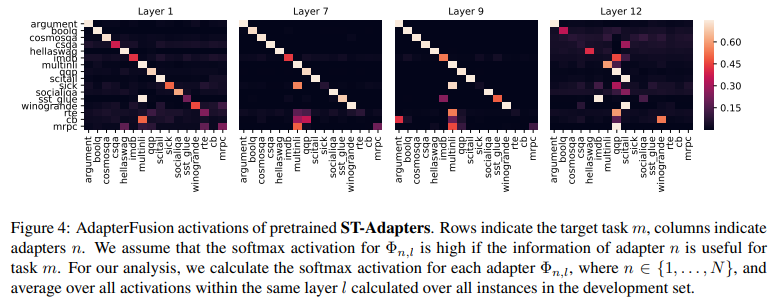

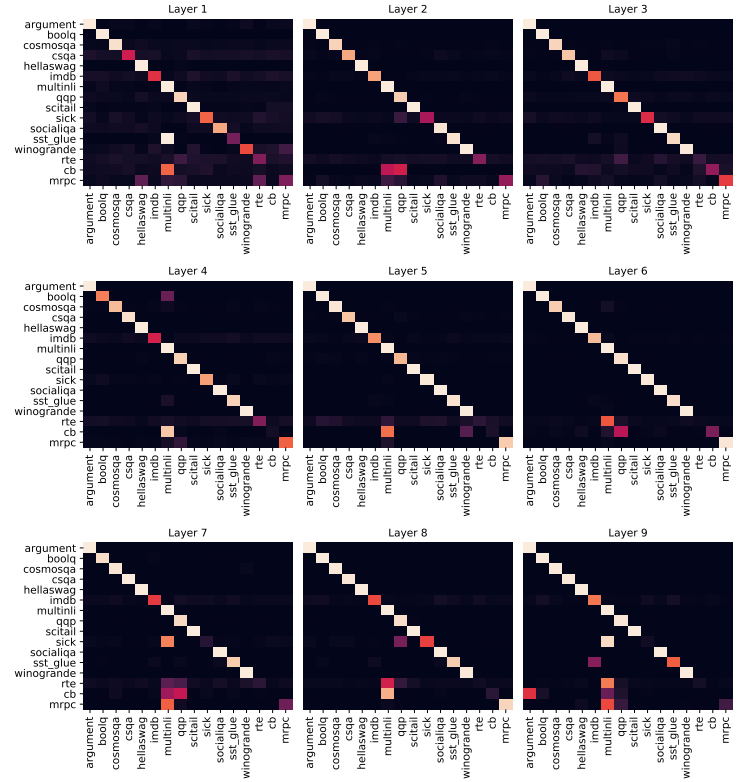

We analyze the weighting patterns that are learned by AdapterFusion to better understand which tasks impact the model predictions, and whether there exist differences across BERT layers.

We plot the results for layers 1, 7, 9, and 12 and ST-A in Figure 4 (see Appendix Figure 6 for the remaining layers). We find that tasks which do not benefit from AdapterFusion tend to more strongly activate their own adapter at every layer (e.g. Argument, HellaSwag, MNLI, QQP, SciTail). This confirms that AdapterFusion only extracts information from adapters if they are beneficial for the target task m. We further find that MNLI is a useful intermediate task that benefits a large number of target tasks, e.g. BoolQ, SICK, CSQA, SST-2, CB, MRPC, RTE, which is in line with previous work (Phang et al., 2018; Conneau and Kiela, 2018; Reimers and Gurevych, 2019). Similarly, QQP is utilized by a large number of tasks, e.g. SICK, IMDB, RTE, CB, MRPC, SST-2. Most importantly, tasks with small datasets such as CB, RTE, and MRPC often strongly rely on adapters trained on large datasets such as MNLI and QQP.

Interestingly, we find that the activations in layer 12 are considerably more distributed across multiple tasks than adapters in earlier layers. The potential reason for this is that the last adapters are not encapsulated between frozen pretrained layers, and can thus be considered as an extension of the prediction head. The representations of the adapters in the 12th layer might thus not be as comparable, resulting in more distributed activations. This is in line with Pfeiffer et al. (2020d) who are able to improve zero-shot cross-lingual performance considerably by dropping the adapters in the last layer.

7. Contemporary Work

In contemporaneous work, other approaches for parameter efficient fine-tuning have been proposed. Guo et al. (2020) train sparse “diff” vectors which are applied on top of pretrained frozen parameter vectors. Ravfogel and Goldberg (2021) only finetune bias terms of the pretrained language models, achieving similar results as full model finetuning. Li and Liang (2021) propose prefix-tuning for natural language generation tasks. Here, continuous task-specific vectors are trained while the remaining model is kept frozen. These alternative, parameter-efficient fine-tuning strategies all encapsulate the idiosyncratic task-specific information in designated parameters, creating the potential for new composition approaches of multiple tasks. Ruckle et al. (2020a) analyse the training and inference efficiency of adapters and AdapterFusion. For AdapterFusion, they find that adding more tasks to the set of adapters results in a linear increase of computational cost, both for training and inference. They further propose approaches to mitigate this overhead.

8. Conclusion and Outlook

8.1. Conclusion

We propose a novel approach to transfer learning called AdapterFusion which provides a simple and effective way to combine information from several tasks. By separating the extraction of knowledge from its composition, we are able to effectively avoid the common pitfalls of multi-task learning, such as catastrophic forgetting and interference between tasks. Further, AdapterFusion mitigates the problem of traditional multi-task learning in which complete re-training is required, when new tasks are added to the pool of datasets.

We have shown that AdapterFusion is compatible with adapters trained in both single-task as well as multi-task setups. AdapterFusion consistently outperforms fully fine-tuned models on the target task, demonstrating the value in having access to information from other tasks. While we observe gains using both ST-A as well as MT-A, we find that composing ST-A using AdapterFusion is the more efficient strategy, as adapters can be trained in parallel and re-used.

Finally, we analyze the weighting patterns of individual adapters in AdapterFusion which reveal that tasks with small datasets more often rely on information from tasks with large datasets, thereby achieving the largest performance gains in our experiments. We show that AdapterFusion is able to identify and select adapters that contain knowledge relevant to task of interest, while ignoring the remaining ones. This provides an implicit no-op option and makes AdapterFusion a suitable and versatile transfer learning approach for any NLU setting.

8.2. Outlook

Ruckle et al. (2020a) have studied pruning a large portion of adapters after Fusion training. Their results show that removing the less activated adapters results in almost no performance drop at inference time while considerably improving the inference speed. They also provide some initial evidence that it is possible to train Fusion with a subset of the available adapters in each minibatch, potentially enabling us to scale our approach to large adapter sets — which would otherwise be computationally infeasible. We believe that such extensions are a promising direction for future work.

Pfeiffer et al. (2020d) have achieved considerable improvements in the zero-shot cross-lingual transfer performance by dropping the adapters in the last layer. In preliminary results, we have observed similar trends with AdapterFusion when the adapters in the last layer are not used. We will investigate this further in future work.

'*NLP > NLP_Paper' 카테고리의 다른 글

Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation (0) 2024.07.27 [LoRA] Low-rank Adaptation of Large Language Models (0) 2024.07.27 [Adapter] Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning for NLP (0) 2024.07.26 Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners (1) 2024.07.26 [CoT] Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models (0) 2024.07.25