-

[GPT-2] Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners*NLP/NLP_Paper 2024. 7. 20. 22:06

Abstract

Natural language processing tasks, such as question answering, machine translation, reading comprehension, and summarization, are typically approached with supervised learning on tasks-pecific datasets. We demonstrate that language models begin to learn these tasks without any explicit supervision when trained on a new dataset of millions of webpages called WebText. When conditioned on a document plus questions, the answers generated by the language model reach 55 F1 on the CoQA dataset - matching or exceeding the performance of 3 out of 4 baseline systems without using the 127,000+ training examples. The capacity of the language model is essential to the success of zero-shot task transfer and increasing it improves performance in a log-linear fashion across tasks. Our largest model, GPT-2, is a 1.5B parameter Transformer that achieves state of the art results on 7 out of 8 tested language modeling datasets in a zero-shot setting but still underfits WebText. Samples from the model reflect these improvements and contain coherent paragraphs of text. These findings suggest a promising path towards building language processing systems which learn to perform tasks from their naturally occurring demonstrations.

1. Introduction

Machine learning systems now excel (in expectation) at tasks they are trained for by using a combination of large datasets, high-capacity models, and supervised learning (Krizhevsky et al., 2012) (Sutskever et al., 2014) (Amodei et al., 2016). Yet these systems are brittle and sensitive to slight changes in the data distribution (Recht et al., 2018) and task specification (Kirkpatrick et al., 2017). Current systems are better characterized as narrow experts rather than competent generalists. We would like to move towards more general systems which can perform many tasks – eventually without the need to manually create and label a training dataset for each one.

The dominant approach to creating ML systems is to collect a dataset of training examples demonstrating correct behavior for a desired task, train a system to imitate these behaviors, and then test its performance on independent and identically distributed (IID) held-out examples. This has served well to make progress on narrow experts. But the often erratic behavior of captioning models (Lake et al., 2017), reading comprehension systems (Jia & Liang, 2017), and image classifiers (Alcorn et al., 2018) on the diversity and variety of possible inputs highlights some of the shortcomings of this approach.

Our suspicion is that the prevalence of single task training on single domain datasets is a major contributor to the lack of generalization observed in current systems. Progress towards robust systems with current architectures is likely to require training and measuring performance on a wide range of domains and tasks. Recently, several benchmarks have been proposed such as GLUE (Wang et al., 2018) and decaNLP (McCann et al., 2018) to begin studying this.

Multitask learning (Caruana, 1997) is a promising framework for improving general performance. However, multitask training in NLP is still nascent. Recent work reports modest performance improvements (Yogatama et al., 2019) and the two most ambitious efforts to date have trained on a total of 10 and 17 (dataset, objective) pairs respectively (McCann et al., 2018) (Bowman et al., 2018). From a meta-learning perspective, each (dataset, objective) pair is a single training example sampled from the distribution of datasets and objectives. Current ML systems need hundreds to thousands of examples to induce functions which generalize well. This suggests that multitask training many need just as many effective training pairs to realize its promise with current approaches. It will be very difficult to continue to scale the creation of datasets and the design of objectives to the degree that may be required to brute force our way there with current techniques. This motivates exploring additional setups for performing multitask learning.

The current best performing systems on language tasks utilize a combination of pre-training and supervised finetuning. This approach has a long history with a trend towards more flexible forms of transfer. First, word vectors were learned and used as inputs to task-specific architectures (Mikolov et al., 2013) (Collobert et al., 2011), then the contextual representations of recurrent networks were transferred (Dai & Le, 2015) (Peters et al., 2018), and recent work suggests that task-specific architectures are no longer necessary and transferring many self-attention blocks is sufficient (Radford et al., 2018) (Devlin et al., 2018).

These methods still require supervised training in order to perform a task. When only minimal or no supervised data is available, another line of work has demonstrated the promise of language models to perform specific tasks, such as commonsense reasoning (Schwartz et al., 2017) and sentiment analysis (Radford et al., 2017).

In this paper, we connect these two lines of work and continue the trend of more general methods of transfer. We demonstrate language models can perform down-stream tasks in a zero-shot setting – without any parameter or architecture modification. We demonstrate this approach shows potential by highlighting the ability of language models to perform a wide range of tasks in a zero-shot setting. We achieve promising, competitive, and state of the art results depending on the task.

2. Approach

At the core of our approach is language modeling. Language modeling is usually framed as unsupervised distribution estimation from a set of examples (x1, x2, ..., xn) each composed of variable length sequences of symbols (s1, s2, ..., sn). Since language has a natural sequential ordering, it is common to factorize the joint probabilities over symbols as the product of conditional probabilities (Jelinek & Mercer, 1980) (Bengio et al., 2003):

This approach allows for tractable sampling from and estimation of p(x) as well as any conditionals of the form p(sn−k, ..., sn|s1, ..., sn−k−1). In recent years, there have been significant improvements in the expressiveness of models that can compute these conditional probabilities, such as self-attention architectures like the Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017).

Learning to perform a single task can be expressed in a probabilistic framework as estimating a conditional distribution p(output|input). Since a general system should be able to perform many different tasks, even for the same input, it should condition not only on the input but also on the task to be performed. That is, it should model p(output|input, task). This has been variously formalized in multitask and meta-learning settings. Task conditioning is often implemented at an architectural level, such as the task specific encoders and decoders in (Kaiser et al., 2017) or at an algorithmic level such as the inner and outer loop optimization framework of MAML (Finn et al., 2017). But as exemplified in McCann et al. (2018), language provides a flexible way to specify tasks, inputs, and outputs all as a sequence of symbols. For example, a translation training example can be written as the sequence (translate to french, english text, french text). Likewise, a reading comprehension training example can be written as (answer the question, document, question, answer). McCann et al. (2018) demonstrated it was possible to train a single model, the MQAN, to infer and perform many different tasks on examples with this type of format.

Language modeling is also able to, in principle, learn the tasks of McCann et al. (2018) without the need for explicit supervision of which symbols are the outputs to be predicted. Since the supervised objective is the the same as the unsupervised objective but only evaluated on a subset of the sequence, the global minimum of the unsupervised objective is also the global minimum of the supervised objective. In this slightly toy setting, the concerns with density estimation as a principled training objective discussed in (Sutskever et al., 2015) are side stepped. The problem instead becomes whether we are able to, in practice, optimize the unsupervised objective to convergence. Preliminary experiments confirmed that sufficiently large language models are able to perform multitask learning in this toy-ish setup but learning is much slower than in explicitly supervised approaches.

While it is a large step from the well-posed setup described above to the messiness of “language in the wild”, Weston (2016) argues, in the context of dialog, for the need to develop systems capable of learning from natural language directly and demonstrated a proof of concept – learning a QA task without a reward signal by using forward prediction of a teacher’s outputs. While dialog is an attractive approach, we worry it is overly restrictive. The internet contains a vast amount of information that is passively available without the need for interactive communication. Our speculation is that a language model with sufficient capacity will begin to learn to infer and perform the tasks demonstrated in natural language sequences in order to better predict them, regardless of their method of procurement. If a language model is able to do this it will be, in effect, performing unsupervised multitask learning. We test whether this is the case by analyzing the performance of language models in a zero-shot setting on a wide variety of tasks.

2.1. Training Dataset

Most prior work trained language models on a single domain of text, such as news articles (Jozefowicz et al., 2016), Wikipedia (Merity et al., 2016), or fiction books (Kiros et al., 2015). Our approach motivates building as large and diverse a dataset as possible in order to collect natural language demonstrations of tasks in as varied of domains and contexts as possible.

A promising source of diverse and nearly unlimited text is web scrapes such as Common Crawl. While these archives are many orders of magnitude larger than current language modeling datasets, they have significant data quality issues. Trinh & Le (2018) used Common Crawl in their work on commonsense reasoning but noted a large amount of documents “whose content are mostly unintelligible”. We observed similar data issues in our initial experiments with Common Crawl. Trinh & Le (2018)’s best results were achieved using a small subsample of Common Crawl which included only documents most similar to their target dataset, the Winograd Schema Challenge. While this is a pragmatic approach to improve performance on a specific task, we want to avoid making assumptions about the tasks to be performed ahead of time.

Instead, we created a new web scrape which emphasizes document quality. To do this we only scraped web pages which have been curated/filtered by humans. Manually filtering a full web scrape would be exceptionally expensive so as a starting point, we scraped all outbound links from Reddit, a social media platform, which received at least 3 karma. This can be thought of as a heuristic indicator for whether other users found the link interesting, educational, or just funny

The resulting dataset, WebText, contains the text subset of these 45 million links. To extract the text from HTML responses we use a combination of the Dragnet (Peters & Lecocq, 2013) and Newspaper1 content extractors. All results presented in this paper use a preliminary version of WebText which does not include links created after Dec 2017 and which after de-duplication and some heuristic based cleaning contains slightly over 8 million documents for a total of 40 GB of text. We removed all Wikipedia documents from WebText since it is a common data source for other datasets and could complicate analysis due to over- lapping training data with test evaluation tasks.

2.2. Input Representation

A general language model (LM) should be able to compute the probability of (and also generate) any string. Current large scale LMs include pre-processing steps such as lowercasing, tokenization, and out-of-vocabulary tokens which restrict the space of model-able strings. While processing Unicode strings as a sequence of UTF-8 bytes elegantly fulfills this requirement as exemplified in work such as Gillick et al. (2015), current byte-level LMs are not competitive with word-level LMs on large scale datasets such as the One Billion Word Benchmark (Al-Rfou et al., 2018). We observed a similar performance gap in our own attempts to train standard byte-level LMs on WebText.

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) (Sennrich et al., 2015) is a practical middle ground between character and word level language modeling which effectively interpolates between word level inputs for frequent symbol sequences and character level inputs for infrequent symbol sequences. Despite its name, reference BPE implementations often operate on Unicode code points and not byte sequences. These implementations would require including the full space of Unicode symbols in order to model all Unicode strings. This would result in a base vocabulary of over 130,000 before any multi-symbol tokens are added. This is prohibitively large compared to the 32,000 to 64,000 token vocabularies often used with BPE. In contrast, a byte-level version of BPE only requires a base vocabulary of size 256. However, directly applying BPE to the byte sequence results in suboptimal merges due to BPE using a greedy frequency based heuristic for building the token vocabulary. We observed BPE including many versions of common words like dog since they occur in many variations such as dog. dog! dog? . This results in a sub-optimal allocation of limited vocabulary slots and model capacity. To avoid this, we prevent BPE from merging across character categories for any byte sequence. We add an exception for spaces which significantly improves the compression efficiency while adding only minimal fragmentation of words across multiple vocab tokens.

This input representation allows us to combine the empirical benefits of word-level LMs with the generality of byte-level approaches. Since our approach can assign a probability to any Unicode string, this allows us to evaluate our LMs on any dataset regardless of pre-processing, tokenization, or vocab size.

2.3. Model

We use a Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017) based architecture for our LMs. The model largely follows the details of the OpenAI GPT model (Radford et al., 2018) with a few modifications. Layer normalization (Ba et al., 2016) was moved to the input of each sub-block, similar to a pre-activation residual network (He et al., 2016) and an additional layer normalization was added after the final self-attention block. A modified initialization which accounts for the accumulation on the residual path with model depth is used. We scale the weights of residual layers at initialization by a factor of 1/ √ N where N is the number of residual layers. The vocabulary is expanded to 50,257. We also increase the context size from 512 to 1024 tokens and a larger batchsize of 512 is used.

3. Experiments

We trained and benchmarked four LMs with approximately log-uniformly spaced sizes. The architectures are summarized in Table 2. The smallest model is equivalent to the original GPT, and the second smallest equivalent to the largest model from BERT (Devlin et al., 2018). Our largest model, which we call GPT-2, has over an order of magnitude more parameters than GPT. The learning rate of each model was manually tuned for the best perplexity on a 5% held-out sample of WebText. All models still underfit WebText and held-out perplexity has as of yet improved given more training time.

3.1. Language Modeling

As an initial step towards zero-shot task transfer, we are interested in understanding how WebText LM’s perform at zero-shot domain transfer on the primary task they are trained for – language modeling. Since our model operates on a byte level and does not require lossy pre-processing or tokenization, we can evaluate it on any language model benchmark. Results on language modeling datasets are commonly reported in a quantity which is a scaled or exponentiated version of the average negative log probability per canonical prediction unit - usually a character, a byte, or a word. We evaluate the same quantity by computing the log-probability of a dataset according to a WebText LM and dividing by the number of canonical units. For many of these datasets, WebText LMs would be tested significantly out-of-distribution, having to predict aggressively standardized text, tokenization artifacts such as disconnected punctuation and contractions, shuffled sentences, and even the string <UNK> which is extremely rare in WebText - occurring only 26 times in 40 billion bytes. We report our main results in Table 3 using invertible de-tokenizers which remove as many of these tokenization / pre-processing artifacts as possible. Since these de-tokenizers are invertible, we can still calculate the log probability of a dataset and they can be thought of as a simple form of domain adaptation. We observe gains of 2.5 to 5 perplexity for GPT-2 with these de-tokenizers.

WebText LMs transfer well across domains and datasets, improving the state of the art on 7 out of the 8 datasets in a zero-shot setting. Large improvements are noticed on small datasets such as Penn Treebank and WikiText-2 which have only 1 to 2 million training tokens. Large improvements are also noticed on datasets created to measure long-term dependencies like LAMBADA (Paperno et al., 2016) and the Children’s Book Test (Hill et al., 2015). Our model is still significantly worse than prior work on the One Billion Word Benchmark (Chelba et al., 2013). This is likely due to a combination of it being both the largest dataset and having some of the most destructive pre-processing - 1BW’s sentence level shuffling removes all long-range structure.

3.2. Children's Book Test

The Children’s Book Test (CBT) (Hill et al., 2015) was created to examine the performance of LMs on different categories of words: named entities, nouns, verbs, and prepositions. Rather than reporting perplexity as an evaluation metric, CBT reports accuracy on an automatically constructed cloze test where the task is to predict which of 10 possible choices for an omitted word is correct. Following the LM approach introduced in the original paper, we compute the probability of each choice and the rest of the sentence conditioned on this choice according to the LM, and predict the one with the highest probability. As seen in Figure 2 performance steadily improves as model size is increased and closes the majority of the gap to human performance on this test. Data overlap analysis showed one of the CBT test set books, The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling, is in WebText, so we report results on the validation set which has no significant overlap. GPT-2 achieves new state of the art results of 93.3% on common nouns and 89.1% on named entities. A de-tokenizer was applied to remove PTB style tokenization artifacts from CBT.

3.3. LAMBADA

The LAMBADA dataset (Paperno et al., 2016) tests the ability of systems to model long-range dependencies in text. The task is to predict the final word of sentences which require at least 50 tokens of context for a human to successfully predict. GPT-2 improves the state of the art from 99.8 (Grave et al., 2016) to 8.6 perplexity and increases the accuracy of LMs on this test from 19% (Dehghani et al., 2018) to 52.66%. Investigating GPT-2’s errors showed most predictions are valid continuations of the sentence, but are not valid final words. This suggests that the LM is not using the additional useful constraint that the word must be the final of the sentence. Adding a stop-word filter as an approximation to this further increases accuracy to 63.24%, improving the overall state of the art on this task by 4%. The previous state of the art (Hoang et al., 2018) used a different restricted prediction setting where the outputs of the model were constrained to only words that appeared in the context. For GPT-2, this restriction is harmful rather than helpful since 19% of answers are not in context. We use a version of the dataset without preprocessing.

3.4. Winograd Schema Challenge

The Winograd Schema challenge (Levesque et al., 2012) was constructed to measure the capability of a system to perform commonsense reasoning by measuring its ability to resolve ambiguities in text. Recently Trinh & Le (2018) demonstrated significant progress on this challenge using LMs, by predicting the resolution of the ambiguity with higher probability. We follow their problem formulation and visualize the performance of our models with both full and partial scoring techniques in Figure 3. GPT-2 improves state of the art accuracy by 7%, achieving 70.70%. The dataset is quite small with only 273 examples so we recommend reading Trichelair et al. (2018) to help contextualize this result.

3.5. Reading Comprehension

The Conversation Question Answering dataset (CoQA) Reddy et al. (2018) consists of documents from 7 different domains paired with natural language dialogues between a question asker and a question answerer about the document. CoQA tests reading comprehension capabilities and also the ability of models to answer questions that depend on conversation history (such as “Why?”).

Greedy decoding from GPT-2 when conditioned on a document, the history of the associated conversation, and a final token A: achieves 55 F1 on the development set. This matches or exceeds the performance of 3 out of 4 baseline systems without using the 127,000+ manually collected question answer pairs those baselines were trained on. The supervised SOTA, a BERT based system (Devlin et al., 2018), is nearing the 89 F1 performance of humans. While GPT-2’s performance is exciting for a system without any supervised training, some inspection of its answers and errors suggests GPT-2 often uses simple retrieval based heuristics such as answer with a name from the document in response to a who question.

3.6. Summarization

We test GPT-2’s ability to perform summarization on the CNN and Daily Mail dataset (Nallapati et al., 2016). To induce summarization behavior we add the text TL;DR: after the article and generate 100 tokens with Top-k random sampling (Fan et al., 2018) with k = 2 which reduces repetition and encourages more abstractive summaries than greedy decoding. We use the first 3 generated sentences in these 100 tokens as the summary. While qualitatively the generations resemble summaries, as shown in Table 14, they often focus on recent content from the article or confuse specific details such as how many cars were involved in a crash or whether a logo was on a hat or shirt. On the commonly reported ROUGE 1,2,L metrics the generated summaries only begin to approach the performance of classic neural baselines and just barely outperforms selecting 3 random sentences from the article. GPT-2’s performance drops by 6.4 points on the aggregate metric when the task hint is removed which demonstrates the ability to invoke task specific behavior in a language model with natural language.

3.7. Translation

We test whether GPT-2 has begun to learn how to translate from one language to another. In order to help it infer that this is the desired task, we condition the language model on a context of example pairs of the format english sentence = french sentence and then after a final prompt of english sentence = we sample from the model with greedy decoding and use the first generated sentence as the translation. On the WMT-14 English-French test set, GPT-2 gets 5 BLEU, which is slightly worse than a word-by-word substitution with a bilingual lexicon inferred in previous work on unsupervised word translation (Conneau et al., 2017b). On the WMT-14 French-English test set, GPT-2 is able to leverage its very strong English language model to perform significantly better, achieving 11.5 BLEU. This outperforms several unsupervised machine translation baselines from (Artetxe et al., 2017) and (Lample et al., 2017) but is still much worse than the 33.5 BLEU of the current best unsupervised machine translation approach (Artetxe et al., 2019). Performance on this task was surprising to us, since we deliberately removed non-English webpages from WebText as a filtering step. In order to confirm this, we ran a byte-level language detector2 on WebText which detected only 10MB of data in the French language which is approximately 500x smaller than the monolingual French corpus common in prior unsupervised machine translation research.

3.8. Question Answering

A potential way to test what information is contained within a language model is to evaluate how often it generates the correct answer to factoid-style questions. Previous showcasing of this behavior in neural systems where all information is stored in parameters such as A Neural Conversational Model (Vinyals & Le, 2015) reported qualitative results due to the lack of high-quality evaluation datasets. The recently introduced Natural Questions dataset (Kwiatkowski et al., 2019) is a promising resource to test this more quantitatively. Similar to translation, the context of the language model is seeded with example question answer pairs which helps the model infer the short answer style of the dataset. GPT-2 answers 4.1% of questions correctly when evaluated by the exact match metric commonly used on reading comprehension datasets like SQUAD.3 As a comparison point, the smallest model does not exceed the 1.0% accuracy of an incredibly simple baseline which returns the most common answer for each question type (who, what, where, etc...). GPT-2 answers 5.3 times more questions correctly, suggesting that model capacity has been a major factor in the poor performance of neural systems on this kind of task as of yet. The probability GPT-2 assigns to its generated answers is well calibrated and GPT-2 has an accuracy of 63.1% on the 1% of questions it is most confident in. The 30 most confident answers generated by GPT-2 on development set questions are shown in Table 5. The performance of GPT-2 is still much, much, worse than the 30 to 50% range of open domain question answering systems which hybridize information retrieval with extractive document question answering (Alberti et al., 2019).

4. Generalization vs Memorization

Recent work in computer vision has shown that common image datasets contain a non-trivial amount of near-duplicate images. For instance CIFAR-10 has 3.3% overlap between train and test images (Barz & Denzler, 2019). This results in an over-reporting of the generalization performance of machine learning systems. As the size of datasets increases this issue becomes increasingly likely which suggests a similar phenomena could be happening with WebText. Therefore it is important to analyze how much test data also shows up in the training data.

To study this we created Bloom filters containing 8-grams of WebText training set tokens. To improve recall, strings were normalized to contain only lower-cased alphanumeric words with a single space as a delimiter. The Bloom filters were constructed such that the false positive rate is upper bounded by 1 / 10^8 . We further verified the low false positive rate by generating 1M strings, of which zero were found by the filter.

These Bloom filters let us calculate, given a dataset, the percentage of 8-grams from that dataset that are also found in the WebText training set. Table 6 shows this overlap analysis for the test sets of common LM benchmarks. Common LM datasets’ test sets have between 1-6% overlap with WebText train, with an average of overlap of 3.2%. Somewhat surprisingly, many datasets have larger overlaps with their own training splits, with an average of 5.9% overlap.

Our approach optimizes for recall, and while manual inspection of the overlaps shows many common phrases, there are many longer matches that are due to duplicated data. This is not unique to WebText. For instance, we discovered that the test set of WikiText-103 has an article which is also in the training dataset. Since there are only 60 articles in the test set there is at least an overlap of 1.6%.4 Potentially more worryingly, 1BW has an overlap of nearly 13.2% with its own training set according to our procedure.

For the Winograd Schema Challenge, we found only 10 schemata which had any 8-gram overlaps with the WebText training set. Of these, 2 were spurious matches. Of the remaining 8, only 1 schema appeared in any contexts that gave away the answer.

For CoQA, about 15% of documents in the news domain are already in WebText and the model performs about 3 F1 better on these. CoQA’s development set metric reports the average performance over 5 different domains and we measure a gain of about 0.5-1.0 F1 due to overlap across the various domains. However, no actual training questions or answers are in WebText since CoQA was released after the cutoff date for links in WebText.

On LAMBADA, the average overlap is 1.2%. GPT-2 performs about 2 perplexity better on examples with greater than 15% overlap. Recalculating metrics when excluding all examples with any overlap shifts results from 8.6 to 8.7 perplexity and reduces accuracy from 63.2% to 62.9%. This very small change in overall results is likely due to only 1 in 200 examples having significant overlap.

Overall, our analysis suggests that data overlap between WebText training data and specific evaluation datasets provides a small but consistent benefit to reported results. However, for most datasets we do not notice significantly larger overlaps than those already existing between standard training and test sets, as Table 6 highlights.

Understanding and quantifying how highly similar text impacts performance is an important research question. Better de-duplication techniques such as scalable fuzzy matching could also help better answer these questions. For now, we recommend the use of n-gram overlap based de-duplication as an important verification step and sanity check during the creation of training and test splits for new NLP datasets.

Another potential way of determining whether the performance of WebText LMs is attributable to memorization is inspecting their performance on their own held-out set. As shown in Figure 4, performance on both the training and test sets of WebText are similar and improve together as model size is increased. This suggests even GPT-2 is still underfitting on WebText in many ways.

GPT-2 is also able to write news articles about the discovery of talking unicorns. An example is provided in Table 13.

5. Related Work

A significant portion of this work measured the performance of larger language models trained on larger datasets. This is similar to the work of Jozefowicz et al. (2016) which scaled RNN based language models on the 1 Billion Word Benchmark. Bajgar et al. (2016) also previously improved results on the Children’s Book Test by creating a much larger training dataset out of Project Gutenberg to supplement the standard training dataset. Hestness et al. (2017) conducted a thorough analysis of how the performance of various deep learning models changes as a function of both model capacity and dataset size. Our experiments, while much noisier across tasks, suggest similar trends hold for sub-tasks of an objective and continue into the 1B+ parameter regime.

Interesting learned functionality in generative models has been documented before such as the cells in an RNN language model performing line-width tracking and quote/comment detection Karpathy et al. (2015). More inspirational to our work was the observation of Liu et al. (2018) that a model trained to generate Wikipedia articles also learned to translate names between languages.

Previous work has explored alternative approaches to filtering and constructing a large text corpus of web pages, such as the iWeb Corpus (Davies, 2018).

There has been extensive work on pre-training methods for language tasks. In addition to those mentioned in the introduction, GloVe (Pennington et al., 2014) scaled word vector representation learning to all of Common Crawl. An influential early work on deep representation learning for text was Skip-thought Vectors (Kiros et al., 2015). McCann et al. (2017) explored the use of representations derived from machine translation models and Howard & Ruder (2018) improved the RNN based fine-tuning approaches of (Dai & Le, 2015). (Conneau et al., 2017a) studied the transfer performance of representations learned by natural language inference models and (Subramanian et al., 2018) explored large-scale multitask training.

(Ramachandran et al., 2016) demonstrated that seq2seq models benefit from being initialized with pre-trained language models as encoders and decoders. More recent work has shown that LM pre-training is helpful when fine-tuned for difficult generation tasks like chit-chat dialog and dialog based question answering systems as well (Wolf et al., 2019) (Dinan et al., 2018).

6. Discussion

Much research has been dedicated to learning (Hill et al., 2016), understanding (Levy & Goldberg, 2014), and critically evaluating (Wieting & Kiela, 2019) the representations of both supervised and unsupervised pre-training methods. Our results suggest that unsupervised task learning is an additional promising area of research to explore. These findings potentially help explain the widespread success of pre-training techniques for down-stream NLP tasks as we show that, in the limit, one of these pre-training techniques begins to learn to perform tasks directly without the need for supervised adaption or modification.

On reading comprehension the performance of GPT-2 is competitive with supervised baselines in a zero-shot setting. However, on other tasks such as summarization, while it is qualitatively performing the task, its performance is still only rudimentary according to quantitative metrics. While suggestive as a research result, in terms of practical applications, the zero-shot performance of GPT-2 is still far from use-able.

We have studied the zero-shot performance of WebText LMs on many canonical NLP tasks, but there are many additional tasks that could be evaluated. There are undoubtedly many practical tasks where the performance of GPT-2 is still no better than random. Even on common tasks that we evaluated on, such as question answering and translation, language models only begin to outperform trivial baselines when they have sufficient capacity.

While zero-shot performance establishes a baseline of the potential performance of GPT-2 on many tasks, it is not clear where the ceiling is with finetuning. On some tasks, GPT-2’s fully abstractive output is a significant departure from the extractive pointer network (Vinyals et al., 2015) based outputs which are currently state of the art on many question answering and reading comprehension datasets. Given the prior success of fine-tuning GPT, we plan to investigate fine-tuning on benchmarks such as decaNLP and GLUE, especially since it is unclear whether the additional training data and capacity of GPT-2 is sufficient to overcome the inefficiencies of uni-directional representations demonstrated by BERT (Devlin et al., 2018).

7. Conclusion

When a large language model is trained on a sufficiently large and diverse dataset it is able to perform well across many domains and datasets. GPT-2 zero-shots to state of the art performance on 7 out of 8 tested language modeling datasets. The diversity of tasks the model is able to perform in a zero-shot setting suggests that high-capacity models trained to maximize the likelihood of a sufficiently varied text corpus begin to learn how to perform a surprising amount of tasks without the need for explicit supervision.5

5Preliminary code for downloading and using the small model is available at https://github.com/openai/gpt-2

8. Appendix A: Samples

8.1. Model capacity

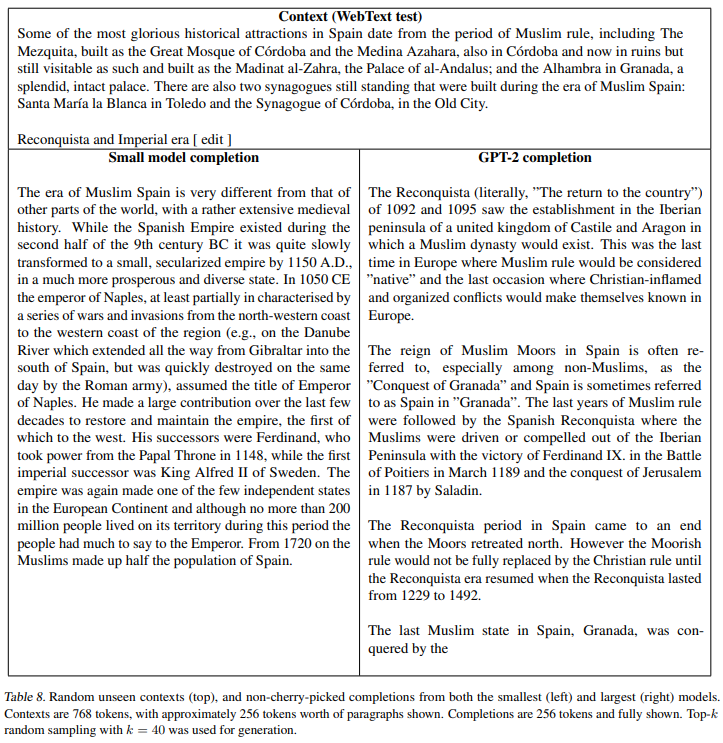

To complement the reported perplexity gains of bigger LMs on WebText show in Figure 4, Tables 7 through 11 show side-by-side completions of the smallest WebText LM and GPT-2 on random unseen WebText test set articles.

8.2. Text Memorization

We observe some memorizing behavior in GPT-2 on longer strings that are repeated many times in the dataset such as famous quotes or speeches. For example, when conditioned on the first sentence and a half of the Gettysburg Address (which occurs approximately 40 times throughout WebText), an argmax decode from GPT-2 recovers the speech. Even when sampling without truncation, we find that the model copies the speech for a while before drifting, albeit in a similar style. It typically drifts within 100-200 tokens, and displays widening diversity once it drifts.

To quantify how often exact memorization shows up in samples, we generated samples from GPT-2 conditioned on WebText test set articles and compared the overlap rates of GPT-2’s generations to the overlap rates of the ground-truth completions. The results of this analysis are shown below and suggest that GPT-2 repeats text from the training set less often then the baseline rate of held-out articles.

8.3. Diversity

Table 12 shows multiple completions of the same random WebText test set context, showing the diversity of completions with standard sampling settings.

8.4. Robustness

Table 13 shows the previously mentioned talking unicorns news article. We find the model to be capable of handling out of distribution contexts, but the quality of these samples is generally lower.

아하하 ^^;; 영어를 구사하는 유니콘을 발견한 것만큼 놀랍네요!

GPT가 배운 적이 없는 유니콘 기사를 영어로 구사하는 게 ㅎㅎ

"I believe, is a sign of evolution, or at least a change in social organization"

유니콘 발견에만 해당하는 건 아닌 것 같습니다 ㅎㅎ

설마.. 이거..

의도적으로 유니콘 예시를 제시한 건 아니죠!!?!?!???

'*NLP > NLP_Paper' 카테고리의 다른 글

[GPT-3] (2/3) Language Models are Few-Shot Learners (0) 2024.07.21 [GPT-3] (1/3) Language Models are Few-Shot Learners (0) 2024.07.21 [BERT] Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding (0) 2024.07.20 [GPT] Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training (0) 2024.07.20 [Transformer] Attention Is All You Need (0) 2024.07.19